1.

Jews in the Netherlands Indies until the Second World War

Jews come to the Dutch Indies

Jews

have never been in the Dutch Indies in great numbers.

In the heyday of the Dutch colonial presence in 1932, there

were around 2000 on 300,000 Dutch colonials, who stayed

among the then 60 million natives.

One of the first Jews was Leendert Miero, who at the end

of the 18th century was soldier on Java and then began a

trade. In Jakarta his grave is still to see. 1a)

Near Banda Aceh there is a Jewish cemetary of Poncut, which indicates Jewish presence there some time 1b)

A

traveller from Jerusalem, Rabbi Jacob Saphir (1822-1886),

who in the fifties of the 19th century on his journey to

collect funds for the Jewish community in Jerusalem also

visited Batavia (Jakarta) mentions in his trip report a

number of 20 Jewish families of Dutch or German origin there.

As the 19th century progressed, there were gradually more

Jews, mainly traders. Well known is the residence of the

journalist Alexander Cohen, the rebel and anarchist, who

moved to the east and for a number of years was a soldier

in the Dutch East Indies Army.

Around

the turn of the century and beyond it was advertised extensively

in the Netherlands to serve in the colonial ranks. Many

Jews responded. During the late 19th century and the first

half of the twentieth century, more and more Jews emigrated

to the colonies. They started a trade, served in the domestic

administration of the colony or in the colonial army, were

active in teaching and medical professions, or were 'planter'

(entrepreneur) in the 'ondernemingen' (extensive plantations

of coffee, tea or rubber ).

My two grandfathers were exemplary for this development.

My grandfather Cassuto emigrated in 1915 to Dutch East Indies

as a young lawyer and teacher (later director of) schools,

educating so-called 'natives' for administrative and managerial

positions.

My grandfather on mother's side van Zuiden, after his education

at the Royal Military Academy in the Netherlands, enlisted

in the Royal Dutch colonial Army, the KNIL. That was in 1905

or 1906. He spent many years in various outposts of the vast

colonial empire.

My

assumption is that my grandfathers were also motivated by

the greater freedom in the colonies. There were no heavy

ties to the Jewish environment and there was less discriminatory

prejudice and more career perspective.

More romantically expressed: the adventure that laid ahead

was less bounded by barriers from the Jewish origin.

In

addition, there was a migration of Jews from the Ottoman

empire to Southeast Asia and some ended up in Sumatra and

Java. In Surabaya, there even a small community of Sephardic

Jews emerged, especially from Iraq. They were called Baghdadi's

and had a modest synagogue, the only one in the then Dutch

East Indies. Later in this story we will encounter them

again.

To

what extent was there a Jewish life in the 'green belt of

emerald'(litterary nickname of the archipelago)?

Said

Rabbi Jacob Saphir who in the 19th century visited the Dutch

East Indies sighed in his report that the Jews there were

hardly practicing their religion anymore. They no more circumcised

their sons and did little to observe the Jewish holidays.

In the twentieth century that still held true.

There was no rabbi in the whole of the Dutch Indies. If

someone insisted on a circumcision of his/her son (brit

mila) you had to hire the rabbi of Singapore.

There was no synagogue, except in Surabaya, where the few

hundred Baghdadi's still were practicing Jewish living.

There were Jews in larger numbers of near one hundred in

Batavia, Semarang and Bandung, but they formed not a real

religious community.

One may ask whether these numbers are correct, because I

suspect that many Jews didn’t profess themselves as

such. In that case, the estimation of 2000 Jews in the thirties

may be on the low side.

My

grandparents lived in the same way as all the other Dutch

colonials.

They were members of the 'Society' (the club of the Dutch

community, nicknamed 'the soos'). They were active in drama

clubs, an journal article preserved by my grandmother reviews

a successful stage performance, which my grandmother appears

to have co-produced.

And an hilarious picture of my otherwise so modest Cassuto

grandfather in his young Indian years shows him dressed

as a woman in the play "The aunt of Charley”,

showing a glimpse from participation in the pleasures of

a carefree life.

They celebrated Christmas and Santa Claus and were involved

in charities or in a variety of celebrations around the

Royal family.

My grandfather van Zuiden is to be seen on photos sitting

at long tables on festive occasions, surrounded by many

more anonymous companions.

The younger brother of my father - like him he was born

on Java - did in an autobiography later in his life retrospect

2) on his experience as a Jewish boy:

"Though

being a Jewish boy my Jewish background meant little to

me. The idea that once others would attach great interest

to it didn’t in the least occur to me ... The fact

that I was Jewish not more impressed me than the fact that

I had two hands, two legs and a nose. It was just a small

part, not worth noticing.”

Later he wrote about the leave time of his family in the

Netherlands (it was 1929 and he was ten years old): "In

Holland, I met my Jewish family and I discovered that they

were quite different than the Dutch colonials. Intuitively

I began to realize that being a Jew meant "being different".

Partly

from sources, partly from hear say, I assume that the Jews

in the Dutch Indies were looking for friends in the Jewish

circle. In the time that my grandfather Cassuto and his family

lived in Bandung, they made many trips to the ‘onderneming’(plantation)

Cigombong, near Bandung on the plateau of Preanger. which

was run by their good friend, the Jewish ‘planter’

Albert Zeehandelaar.

Other suspected Jewish families figure in photo albums.

So my grandfather Cassuto met with my other grandfather

van Zuiden, when the latter after many wanderings on military

posts in the outer regions was stationed in Bandung in an

administrative function.

They were good friends.

Both were members of the Masonic lodge of Bandung.

Many

Jewish residents of larger cities in the Dutch Indies were

members of a Masonic lodge. This should be further investigated.

Although the vast majority of Jews were no longer practicing

Judaism, they had a need for to discuss the deeper things

of life, to philosophize and to celebrate certain events

together. The lodge offered of course not only to Jews but

also to others this opportunity to meet kindred spirits

in a free atmosphere. In those meetings many contacts were

made, also between Jews themselves. Sometimes even Jewish

celebrations were held. I met a man at the symposium, which

like me had lived as Jewish boy in Bandung. He was a few

years older than me and he could remember that in the Freemasons

Lodge Christmas as well as Chanukah was celebrated.

Without doubt, the lodge also offered many opportunities

for what we now call 'networking'.

Also

Zionism attracted the attention of the Jewish residents

of the East. There seems to have existed a periodical from

1926 until the Japanese occupation, called 'Erets Israel’.

Worth further investigation.

1)

Symposium on December 1 2005 on Jews and antisemitism in

the Dutch Indies and in Indonesia, organized by the Foundation

Chair of special Jewish Studies (University of Amsterdam)

by Evelien Gans, professor Contemporary Jewry, in cooperation

with the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation and

the Free University of Amsterdam.

1a) See the article of Rotem Kowner in the frame work of the symposium in Haifa in 2010

1b)

Een Aceh'se kennis vertelde mij:"in the Jewish History Museum in Amsterdam there are photographs of the Jewish cemetary of Pocut, at Banda Aceh (the collection of Clara Brakel of 1979). This is very interested. I remembered when I was still child. I and my friends often went there and looked for Jangkrik. I ever also saw several Dutch who went there.

The photographs of the Jewish cemetery of Pocut (the collection of Clara Brakel) are difference with the photographs that I took pictures in 2004. In 1970s the condition of the cemetery was still good and different with the condition of the Jewish cemetery in 2005. The names of several graves have lose, and the stones of the graves have broken.

The area of the Dutch cemetery, including the Jewish cemetery located in the Desa (Village) of Blower, Banda Aceh. I was born and lived in Blower. The name of Blower derived from a name of Tuan Tanah (absentee landlord), Mr Bolchover. He was a Dutch Jew. He died in Netherlands. When I conducted research there in 2004 and 2005, I did not find the name of Bolchover at that Jewish cemetery.

2) Ernest Cassutto, The Last Jew of Rotterdam, Whitaker

House, 1974. It is an evangelically colored writing about

the conversion of the writer to Christianity in the Second

World War. It was subsequently edited by one of his sons,

but I quote the original version.

2.

Jews in the Dutch Indies during and after the Second World

War

the

outbreak of the Second World War

The

Jewish colonists in the Dutch Indies in the first decades

of the last century lived a relatively carefree and luxurious

life. They lived in beautiful villas with many servants

around them. My parents had a wonderful childhood. “Oh,

Indonesia! How safe and beautiful you were - so many miles

and years away", sighs my father's brother later in

his autobiography. The two brothers had a wonderful childhood.

Also, he writes: "As a Jewish boy my Jewish background

meant little to me. The idea that once some others would

attach so much importance to it didn’t occur to me.

"

Dark

clouds loomed over the tropical paradise but most seemed

successful in ignoring them. An alarming happening, of course,

was the invasion of the Germans into the Netherlands. A

letter from my father from 1945 contains a compelling testimony

of the shocking news.

My father had after his studies in the Netherlands just

arrived in Batavia (Jakarta) and had a job as an administration

official; he was working at the telex, when in came in May

1940 the report of the German invasion; he describes it:

"On

May 10, 1940 I was in Batavia in the Office to the Assistant

Resident (province governor). Wednesday, May 8, when I asked

if I could spend the weekend in Bandoeng, the assistant

governor said that given the situation in Europe he could

not allow this. Friday May 10 about 11 hours o’clock

we got the message of the invasion of Holland. Immediately,

all suspect elements, who should be arrested, should be

put behind bars, and then in about 2 hours the message was

to be made public.

We worked, in shifts, day and night at the office. All kinds

of people gathered at our office offering cooperation and

financial gifts. Some Arabs donated e.g. 5000 Dutch guilders

as a contribution to the war. Small old Indonesian men asked

to be sent to Holland to join the fight. Many who actually

could not afford it brought gold and silver objects. Great

was the anger against every one who claimed themselves ‘NSB-er’

(supporter of the National-Socialist party): Deutsche Klub

in Bandung and the NSB clubhouse on Naripan road were destroyed

by the Bandung schoolchildren."

In

the Dutch Indies life returned to the old routine. However,

the young Dutch men were called into military service and

were given military training.

My parents - both born and raised in Java – had as

a young married couple returned to the Dutch Indies at the

end of 1939 after a Dutch interlude of several years of

study; my father began as a young civil servant in the colonial

administration, but soon after his arrival he too had to

comply to being called into military service for some months

of training for officer.

The

colonial community liked to believe, that the new world war

would pass by the ‘Belt of Emerald’ (as a writer

named the Indonesian archipelago). At the end of 1941, this

unbridled optimism finally dashed. Instead was the sudden

bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7 1941. At the same time

the Japanese armies attacked Singapore. On December 8 the

Dutch government declared war on Japan. The Japanese army

invaded the Dutch Indies on January 10 1942. Singapore fell.

After a short, courageous and hopeless endeavour to defend

the vast empire of thousands of isles the Dutch colonial army

surrendered on March 8 and the Japanese occupation began.

Military prisoners of war were largely employed as slave labourers.

A large group, including my father, was transported under

inhuman conditions to Burma and Thailand to construct a railway

through the jungle - the infamous Burma railway -. Other men

and women and children of European descent were interned in

civilian camps across Indonesia.

What

about the Jews in this turbulent time?

Initially

it was no issue for the Japanese, Jewish or non-Jewish.

In the beginning it was even an advantage. The Japanese

regarded the Jew as 'Asian’ and they let him in alone.

Particularly the Baghdadi in Surabaya will have profited

from this view.

To

my opinion many assimilated Jews didn’t disclose themselves

as Jews to the Japanese, if only because they no longer

felt identified with Judaism. They felt themselves before

all Europeans, mere Dutch nationals and they behaved themselves

as such.

So did my mother and her parents, who in the beginning of

1940 after years of retirement in the Netherlands had decided

to visit their newly married daughter in the Dutch Indies.

By this action, my now since long retired grandfather and

his wife escaped the Germans hunting for the Jews and my grandparents

certainly have saved themselves from the gas chambers just

to fall prey to starvation by the Japanese. On their identity

card issued by the Japanese occupiers was to be read: 'Bangsa'(race,

nationality): totok Blanda (born in the Netherlands, pure

Dutch). Although their journey to the then Dutch East Indies

was to my opinion actually a flight they never defined it

as such, but I presume this escape motive will have surely

been going through the head of my sober and realistic grandfather.

Other Jews who decided to escape from the Germans in the Netherlands

- and also from Germany, Austria and other European countries

- fled to the Dutch Indies, be it at a more leisurely way

during the late thirties or in panic during the outbreak of

war in Europe. An example is Lydia Chagoll, who describes

how in 1940 as a young girl she and her sister came with her

parents from Brussels via a long escape route through France,

Portugal, Mozambique, South Africa, eventually arriving in

Batavia (Jakarta) and finally ending up in a Japanese camp.

We will deal with her book in a while.

In

the course of 1942 the Japanese sealed off areas with barbed

wire (kawat) and plaited bamboo walls (bilik, gedek) transforming

them to internment camps and drove the white women and children

there together. And before it was summoned to go in the camps

many went voluntary, like my mother. She was born in the Dutch

East Indies, and initially there was no need but she nevertheless

preferred to go into to the camp - in this case the Bandung

quarter Cihapit -, where her mother, friends and acquaintances

also already were and where it was safer than outside the

camp.

Japanese

attitude towards the Jews

The

average Japanese soldier had no idea of what a Jew was,

perhaps some officers were more aware of it. Initially,

there was no official policy implying a discriminatory or

special treatment of the Jews. The Japanese actually had

nothing against the Jews.

Japan

itself absorbed even a large group of Jewish refugees.

Over two thousand Jews in possession of papers, provided

by the Dutch consul in Lithuania Jan Zwartendijk and Japanese

diplomat Chiune Sugihara, consul general in Kovno, Lithuania,

had traveled through Siberia and the Far East aiming to

go to America. They were stranded in Japan.

The Japanese were both hospitable as intrigued by the refugees.

In particular, the rabbis and yesjiwa (Judaic college) students

looked strange to them. Members of the Photography Club

Tanpei made photographs of the picturesque refugees; the

photos were exhibited under the title: the wandering Jew.

One of the photographers in a photo magazine wrote in its

portrait of a yesjiwa student:

"How the eyebrows of the displaced man express not

only grief and misery ... but also the tenacity of a people

desperate and scattered about the world. However, they can

not hide their sorrow. They fight in order not to be beaten".

After the war most refugees remembered how interested the

Japanese were and how they were not possessed with anti-Semitism

and didn’t subject them to anti-Semitic treatment,

which in pre-war Poland too many had experienced.

Some, about a thousand of them, before the attack on Pearl

Harbor, could still reach the U.S. and Canada.

In the autumn of 1941 the others were deported to Shang Hai,

where more than twenty thousand other Jewish refugees had

sought refuge. There they formed a ghetto, where life was

difficult, but despite that there were more than 50 newspapers

and magazines in Polish, German and Yiddish. The history is

available on the website of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Jews

must report

The

relatively mild attitude towards the Jews of the Japanese

occupiers of the Dutch Indies underwent in the course of

1943 a change. As a gesture to the German allies the Japanese

authority called upon the Jews to report. 1a)

According

to Jacques Presser in his Dutch book about the persecution

of the Jews in the Netherlands and the colonies this attitude

change was put in motion after a visit by a German consultant

Dr. Wohltat (what's in a name) to Java. This consultant had

to point out to the Japanese allies how dangerous the Jews

were and that they should no longer be left alone. Those who

obviously were Jews (Iraqi Jews for example) and those who

gave ear to the call disappeared in camps (also the Freemasons),

some already were. The Japanese lacked the German ‘Gründlichkeit’;

many 'stateless persons' remained undisturbed.

The

Japanese were probably wondering why the Germans were so obsessed

by the Jews. Presser reported, that in one camp - it is not

stated which - some ten Jews had been compared to the caricatural

images in the Stürmer journal – it did not work

out. When a Jew died, his funeral was performed with the required

ritual. It proved particularly difficult to convince the Japanese

that not all Americans were Jews and that Roosevelt, whose

mother was called Sarah, was not.

In general the treatment of Jews in the camps seemed to have

deviated little from the treatment of the others in the camp

Cimahi if only they were allowed to wash their clothes less

often. 2)

My

mother had to report as a Jewess but she did not. She has

told me that she felt that the Japanese attached little value

to it and therefore nobody noticed her disobedience. Many

assimilated European Jewish women (maybe some men at Cimahi

camp) will have followed the same line.

As for the camp experience of my grandmother, my mother

and me, we were in the same boat as the other European women

and children. Elsewhere I have written about. 3)

camp

Tangerang

Those

Jewish women who had reported as Jewish came into the camp

Tangerang, just west of Batavia (Jakarta). Part of the camp

was intended for Jews.4) Memories of the camp Tangerang

and Adek (the camp where in the end of the war residents

of the camp Tangerang were to go) are to be found in the

book "Camp memories” of Miep Bakker 5). She mentions

in her preface, that "Jewish women were brought in."

She did not mention a separate department. But she mentioned

a number of events featuring Jewish women such as Ms Cohen

who got beautiful curls in her hair after an attack of typhus;

and then there is the young Jewess who had lived for years

in Japan and who was now acting as an interpreter whispering

in the ear of Miep Bakker not to go in discussion with the

angry Japanese commander.

For

a description of the camp from the Jewish experience I make

gratefully use of the book "Six years and six months”

of Lydia Chagoll 6).

She came with her family from Brussels, arrived after many

wanderings in the Dutch Indies and her mother had reported

as a Jewess after the summons of the Japanese. From the

Tjideng camp, where they first stayed, she was transferred

with Lydia and her sister to Tangerang.

There was, Lydia recalled, a Christian section and a Jewish

section, where Jews lived of all nationalities, religious

or not, in various big rooms, also women who were married

to Jews were housed there, for example there were also a

Javanese with her two daughters and a Chinese with her child.

There were also European Freemason women.

musical

prisoners

The

only man besides the doctor who stayed as a prisoner for

a long time in the camp was the famous violinist Szymon

Goldberg. He fled Nazi Germany in 1933. He was on tour in

the Dutch Indies with his wife, also a pianist, and the

equally famous piano virtuoso Lily Kraus. All three were

interned in Tangerang. Goldberg and his wife had a separate

room assigned, stirring the jealousy of other women. Occasionally

they gave a concert for the Japanese commander. The camp

internees could have been and could just as prisoners are

forgotten.

After a few months Szymon Goldberg was transferred to another

camp. His wife was moved from the separate room to the public

sleeping room, her bed was opposite that of Lily Kraus.

Lily

Kraus lived completely isolated from other women. The other

women considered her completely crazy, because they did

yoga, reports Lydia Chagoll.

Miep Bakker tells how at a certain moment in the hangar

that had served as a gym a big black piano was put down.

Lily Kraus was required to study every day. Once a month

she was to give a concert, which actually happened a few

times. Miep Bakker tells how during lost hours she had been

sitting in the corner of the entrance to the hangar listening

to her full delight to the piano sonatas of Mozart, where

the pianist was world famous for.

Szymon Goldberg and Lily Kraus have survived the war and

have continued their career, Kraus despite the damage to

her hands.

the

‘Irakers'

A

shed in the Jewish section was populated only by Iraqi Jews

in Surabaya, the Baghdadi's' that we already ran into.

Please let me quote Lydia Chagoll in her vivid description

of this very special camp residents:

'Irakers!

Temperamental people, some dressed as gypsies. No one ventured

a step in the Iraqi barracks, which also during daytime

remained shrouded in mysterious darkness. It was always

noisy. There was always something going on. In loud voices

they gave expression to their moods. They came regularly

to blows. With an infernal noise, crying and shrieking,

they fervently beat one another with whatever was on hand.

When there was there nothing they went to fight with bare

fists, even with the teeth. If one of them, however, was

attacked by another camp resident than they stood as one

man, a strong power, a united group. At that moment it was

wiser not to interfere, it was wiser not to look, quite

probably you would catch an unintended blow. No, it was

best to stay as far as possible.

The Irakers preferred to deal with only their own group

members.

A few tried to be their friend, but everybody avoided to

be their enemies."

The

Japanese did not know very well how to cope with the Iraqi

Jews. Chagoll:

'It was on the advice of the Germans that the Irakers had

been transferred from Surabaya to the Tangerang camp with

its Jewish section. But the Japanese were puzzled. The lrakers

looked physically so different and behaved so differently

in comparison with the other camp residents. The Irakers

were not Westerners, not Europeans, not whites. The white

skinned Europeans were worthy of their contempt, but not

the Irakers not so!"

Notwithstanding

the Iraqi division was likely the most religiously observant

place throughout the archipelago. There was even a kosher

kitchen! The striking description of Chagoll:

"Maybe because the Japanese accepted Irakers as non

Europeans, or in order to bully the whites, or because there

were not enough guards to contain the Iraqi furies, or in

order to frustrate the Germans who were in spite of all

still white skinned, or simply not to stir ‘soesa’

(troubles), the Japanese gave in to urgent requests of the

Irakers and provided them with a kosher kitchen.

Only the Iraqi community was officially observant of the strict

Jewish religious laws. To live accordingly was something else.

That had to be taken with a grain of salt and a pinch of salt

of very rough quality. The other Jewish population in the

camp, with a few exceptions, was quite liberally oriented.

So Irakers wanted a kosher kitchen. The Irakers were so

convinced of their right that they could move mountains

to reach their goal. There came a kosher kitchen. A totally

separate kitchen service, only controlled by them from the

onset till distribution. "

Lydia

suspected probably not wrongly that the kosher kitchen also

was a good opportunity for processing smuggled food.

Adek

camp and capitulation

In

the spring of 1945, the whole camp has moved to Adek, a

building in Batavia (Jakarta). Lydia Chagoll painted in

a brief paragraph the inhabitants of her shack:

"Part

of the Jewish Diaspora was united in our Adek shed. A small

Palestine without men. There were nine countries represented:

Netherlands-Belgium-Austria-Germany-France-England - Romania-Iraq-China

and of course the Dutch lndiës. All together some fifty

women, with or without children. Housewives, lawyers, nurses,

beauticians, prostitutes, office clericals, sales, seamstresses,

business women. Together we shared a continuous bed. Everyone

was entitled to fifty centimetres. It was a small hut, about

9 to 5 meters. The group did well. I can not remember quarrels,

only small frictions. Together we tried to make the best

of it, interfering as little as possible with each other."

Chagoll

proceeds with her personal story of exhaustion, hunger,

disease and apathy, and finally the liberation in August

1945, which was not liberation, repatriation in April 1946

and the difficult adjustment to European life. The story

of many children. Including mine, which is reported elsewhere.

In

summary we can say that a small part of the Jews in the Dutch

Indies has been interned separately as Jews, and they have

been treated as bad - not worse – as the non-Jewish

internees in other camps including the assimilated Jewish

women, children and some men (like my grandfather held captive

in the Cimahi camp).

What

happened to the Iraqi Jewish men from Surabaya after the

capitulation has happened I do not know and it would be

worthwhile to investigate how they fared and how for them

the turbulent post-war years have been.

Among

the soldiers made prisoners of war and forced to perform slave

labour, such as at the Burma railway, there will also have

been a number of Jewish men, my father was one of them.

To my knowledge, the Japanese made not a case of special

selection of Jews.

Indonesia

After

the war most Jews of European stock had to live through the

post-war turbulence (called the Bersiap period) such as the

independence struggle of the Indonesians and this anarchic

period with its robber gangs made many victims.

Many Jewish families had lost their homes and possessions

and returned to Europe and the Netherlands.

Some stayed in Indonesia.

In the fifties there still seemed room for Jewish presence

and there began to dawn a perspective. According to Beth Ha-Tefoetsot

(diaspora museum in Tel Aviv) there were in 1957 450 Jews

in Indonesia, in Jakarta and Surabaya, Ashkenazic (north and

easteuropean) Jews and Sephardic Jews (Iraqi).

Especially

the Sephardic community in Surabaya started to bloom.

Oral witnesses 7) gave an optimistic picture of the fifties.

They say in this period thousands of Jews lived in Surabaya,

and that the center of the city was dominated by them like

by the Chinese today. The community had acquired a new synagogue

and had made a badminton court behind it. The youth did

in sports, studied the holy writings and learned Hebrew,

they celebrated the holidays and celebrations of life with

their family. But this glory would not last long.

When

in the beginning of a 60-years the New Guinea affair stirred

nationalist and anti-Dutch sentiments, still many left Indonesia.

Many Jews emigrated to the United States, Australia and

Israel. In 1969 there were 20 Jews in Jakarta and Surabaya

25.

Some

went to Israel and form a somewhat lost group. "The Dutch-Jewish

immigrant community doesn’t understand the immigrants

from Indonesia and has no desire to," says Shoshanna

Lehrer 10), the initiator of the association of Israeli’s

with an Indonesian past "Tempo Dulu" ( "ancient

times”). 4 to 5 times per year there is a gathering

with a lecture or so about Indonesia and each member brings

something for the Indonesian food dinner. The members fall

roughly into three groups: Dutch Jews, Jews from the Baghdad

community of Surabaya and former refugees mainly from Germany

and Austria.

Now

there are only a few Jews on: 20 in Surabaya, the remainder

of the Iraqi community, and perhaps a few individuals in

Jakarta.

The synagogue in Surabaya is still there. 8)

In the colonial era a Dutch doctor lived there. His house

was purchased in 1950 and rebuilt. The outside of the synagogue

is white. Inside it is an undeniable orthodox Sephardic

synagogue.

The simple Holy Arke is empty now and the Torah scroll has

been moved to the larger community in Singapore.

There is no rabbi or teacher anymore.

In the case of the desk a clutter of books is to be found,

including pre-war Dutch books, prayer books of the army

from the Second World War, and shiny new prayer books, sent

by a Sephardic institution in New York.

antisemitism

During

the past anti-Semitism among the Indonesian population has

played no significant role.

That has changed in recent years.

Judaism is not a recognized religion in Indonesia. There

are six recognized religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism,

Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism. The compulsory identity

card should contain one of these religions. Inter-religious

marriages are prohibited.

As

an effect of the radicalization of Islam, reinforcing the

political division between east and west, a new type of anti-Semitism

has developed in an increasing number of Indonesians, in which

Judaism, Israel and America is taken as one phenomenon and

is viewed as the major evil opponent with one name: Yahudi,

Jew.

The

myth of the Jewish world conspiracy is back in Indonesia and

the archetypal anti-Semitic writing, the 'Protocols of the

Wise Men of Zion' is freely available. I can only hope that

this virulent anti-Semitism will be confined to a small minority

of the population.

Leah

Zahavi, one of the remaining Iraqi Jews in Surabaya, who

maintains the synagogue and receives guests, is afraid –

in this period after Suharto and his ‘Order Baroe’

– that because of the fragmentation of the social

order and the emergence of militant Islam the situation

for herself and her few fellow Jews will deteriorate. For

friends and neighbors she doesn’t hide her being a

Jew, but in daily affairs and if the going gets rough she

prefers to pass as an Arab.

RC

Feb. 22. 2007

Postcript oct. 2010

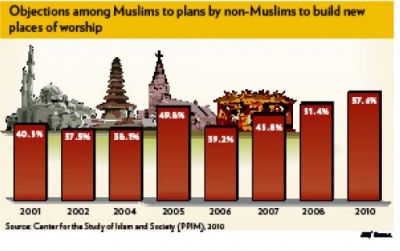

The following observation (from the Jakarta Post of 4 oct. 2010) bconfirms the increasing intolerance for other religions in Indonesia: "The survey showed that non-acceptance levels among the surveyed Muslims toward the construction of churches and other non-Muslim religious buildings in 2010 was 57.8 percent, the highest ever recorded since 2001 (40.5 percent)."

source: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2010/09/29/intolerance-‘-rise’-among-muslims.html

notes

1)

the history is told as a very interesting summary on the

website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

1a) uitgebreid over japans antisemitisme in de tweede wereldoorog in Indonesie en de invloed van de Duitsers daarop in artikel van prof. Rotem Kovner, The Japanese internment of Jews in wartime Indonesia and its causes, 2010

2) Dr. J. Presser, Ondergang, State Publishing, 1965, p.

451-452;

the entire book is available on the Internet including the

covered passage

3) For example, Japanese camp Moentilan in Central Java

and the reconstruction of my stay there in the article 'Moentilan'

4) In fact, there were in and near the town of Tangerang

three places, which for a long time have served as camp,

the prison, the youth prisons and the re-education building.

Probably Lydia Chagoll means the latter place, see Illustrated

Atlas of the Japanese camps 1942-145, Asia Maior, 2000.

5) Miep Bakker, Camp Memories, life in the Japanese camps

Tangerang and Adek, home edition

6) Lydia Chagoll, Six years and six months, Standard Publishers,

Antwerp, 1981

7) A description of the history and situation of the Jews

in Surabaya I found on the Internet: an article 'The Jews

of Surabaya' by Jessica Champagne and Teuku Cut Mahmud Aziz,

in Latitudes Magazine

8) on the site of Beth HaTefoetsot (the Diaspora Museum in

Tel Aviv) there are 2 more photos of the cemetery in Surabaya

and the Holy Arke (Aron ha-Kodesh)

10): "Hollands Glorie in the Holy Land" by William

Dercksen in Jewish News, winter 06